1 Great George street Roseau after Hurricane Maria. Photo by Yuri A Jones www.yuriajones.com

Three years ago, the skies over the island nation of Dominica darkened, powerful winds picked up, and waves began crashing onshore with great intensity. Unknown to the people of Dominica, Hurricane Maria was gearing up to make landfall on the southwest coast of the island, a hurricane event that would eventually leave 31 people dead, 37 missing, and destroy more than 90% of the island’s infrastructure. Dominica boasts beautiful mountain vistas and 365 rivers, one for every day of the year, but the same steep terrain and rivers which were the pride of the island nation made it extremely vulnerable to the torrential downpour which bolstered overflowing rivers and caused flash floods. The catastrophic scale of the damage forced a country that has done very little to contribute to global climate change to reckon with its fierce consequences.

Many remember the night of Hurricane Maria vividly. The storm quickly intensified from a Category 3 as most expected, to a Category 5 hurricane, and could never be prepared enough for what was to come. In the pitch darkness, the intense gust blew over the island. Many related the sound of the winds, to loud trains, forcefully coming at full speed through an underground tunnel. Others said they heard screams of spirits through the winds, calling the Hurricane “an evil force”. Roofs ripped off homes, the streets flooded, and citizens took refuge where they could, hoping that they would see the sunrise in the morning and the storm is gone. Maria finally passed over Dominica by the next morning and headed up the Antilles, towards St Croix and Puerto Rico. The winds subsided, the next morning, as people crawled out of their damaged homes, and it looked like an apocalyptic movie scene. The country was wrecked as if a bomb had gone off. Roads were blocked, the electricity and telecommunication grids severely damaged, demolished bridges, buildings left uninhabitable, ports destroyed, and the economy broken (images 1&2). Here was a land, so luscious and green just the day before, now stripped bare, brown and barren. (Click for Drone imagery of damage immediately after Hurricane Maria).

2 Old Street Roseau following Hurricane Maria. Photo by Yuri A Jones www.yuriajones.com

Despite the ominous signs leading up to Maria’s landfall (dark clouds, heavy rainfall, and increased wind speed), many Dominicans were initially no more concerned than usual. They were no strangers to hurricanes since Dominica is situated in the middle of the Leeward Island chain in the Eastern Caribbean. The Caribbean is subject to hurricanes that form over the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean and prevailing wilds push them to the West to the Caribbean Sea. In 2015, Tropical Storm Erika moved over the island, leaving about one foot and a half of rain in less than 24 hrs.! Flash floods and landslides were set off in many communities across the island. The village of Petite Savanne in the southeast suffered the greatest as, sadly, parts of the mountain swept down in massive landslides causing the major loss of life and property.

September 18th, 2020, marked the third anniversary of Hurricane Maria, and while that day was one of sadness over the lives lost and devastation caused by the hurricane, it is also now a time of reflection; a moment to think of how far the country has come in terms of building hurricane resilience.

The Path to Recovery – Building Hurricane Resilience

Like diamonds transformed by the application of intense pressure, Dominica is on its way to becoming one of the most resilient rocks in the Caribbean.

3 One of the new resettlement communities built by the government, Cotton Hill Resettlement community in Portsmouth, Dominica. Drone image by Yuri A Jones www.yuriajones.com

Most look at resilience as the ability to “spring back” after a disaster. Natural hazards like Hurricane Maria are not only devastating to human life and property but also affects the economic sectors of developing nations for years to come. Resilience also emphasizes the need for islands to not just be able to rebuild but to reinforce. Islands like Dominica aim to rebuild all sectors stronger– to be able to withstand even higher levels of shock and disturbance from natural hazards. This is its ecological resilience.

Conversations around resilience spark questions about socio-cultural ramifications. For instance, if a fishing village has to be re-located, how does that affect the cultural dynamic of the people? (Images 4&5) Looking at Petite Savanne again, many people had to abandon their homes after Tropical Storm Erika, families divided and living all over the island, and many state that they are still struggling to recover. According to an interview with a villager of Petite Savanne two years after the storm “it is difficult to leave a place that you have been in love with all your life”. As a farmer and fisherman, while he left for a short while after TS Erika, he has since returned to the village. Can communities of people be relocated from high-risk hazard zones without affecting culture drastically? (Image 3) How soon can agriculture and tourism bounce back after a hurricane? Natural disasters rock the stability of a country at several levels.

4 Fishermen bringing in their catch of the day to the village of Scott’s Head. Photos by Dominican photographer Yuri Jones https://www.instagram.com/yuriajones/

5. Fishing village in Dominica Photo by Dominican photographer Yuri Jones www.yuriajones.com

Apart from our ability to bounce back, however, what measures have been put in place to make the country less vulnerable to future storms? Looking at things from a local level, we aim to look at the changes that have been implemented to the way houses are built, the structure of the buildings, and reinforcement measures that would better enable them to withstand hurricane-force winds. The topic of relocation is particularly important (Image 3). While the government has pinpointed areas as high-risk zones and has allocated land for the relocation of these individuals, some still choose to remain and rebuild in these vulnerable areas. This starts the conversation of what local attachment to the land exists among the people of these areas, as well as the drive that would cause someone to prefer to rebuild in high-risk areas rather than to relocate. How do we then go about mapping vulnerabilities and resilience of the country and explaining the perspectives of those most affected?

Hazard Mapping – The Caribbean Cyclone Cartography (CCC) Project & Mona Geoinformatics Institute (MGI)

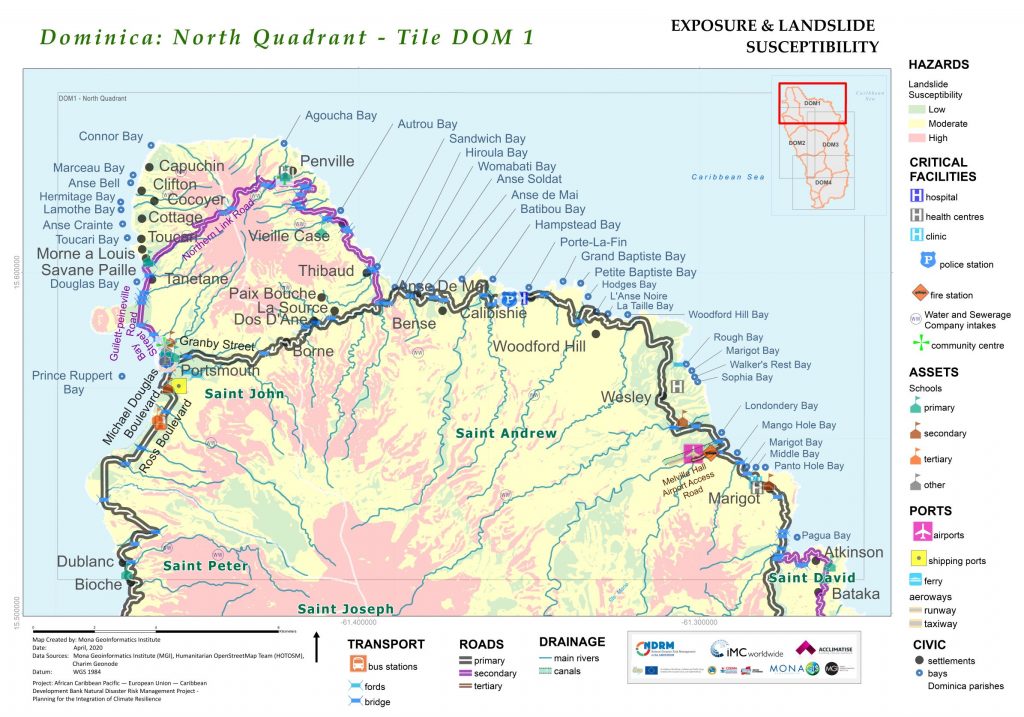

6 Landslide Hazard maps of Dominica, produced by MGI in association with IMC for the ACP EU CDB NDRM Project – Planning for the Integration of Climate Resilience.

The Project

Hurricanes/storm surges, landslides, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and flash flooding are the main natural hazards that pose threats to Dominica (see image 6). The primary focus of the Caribbean Cyclone Cartography (CCC) Project is on the impact of hurricanes and mapping past and present recoveries and resilience in the face of storm events. The CCC project is a collaboration between the Mona GeoInformatics Institute and the Goldsmiths University of London. September 2020, 3 years on from Maria, marks the beginning of an exciting 30-month research journey.

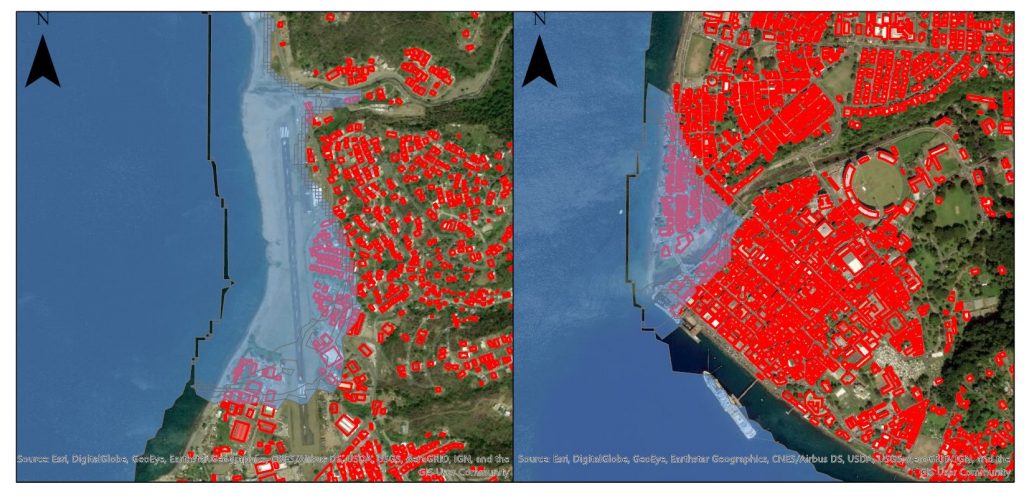

Having a high level of GIS and hazard assessment expertise, the team at MGI will lead the hazards mapping and analysis element-Work Package 5: Mapping Hurricane Resilience – of the CCC project. MGI Deputy Director, Dr. Ava Maxam, leads the CCC project WP5 and supervises Dominican GIS Research Associate, Gabrielle Abraham. The focus will be on identifying vulnerable communities, relocation since Hurricane Maria, infrastructural resilience and recovery, as well as resilience at the individual and community levels. The team will create many multi-layered maps that will answer key questions and tell the stories of survival and recovery in Dominica. MGI is no stranger to hazard mapping and contributing to the decision-making process of emergency planning and resilience strategies across the Caribbean region. Hazard Mapping is an important tool that can create simulations of natural hazards, for example, flash floods, and illustrate who will be the most at risk (image 6&7). This information could sometimes mean life or death to people who have built within flood plains near rivers in Dominica. Additionally, by creating interactive multi-layered maps (incorporating images, videos, and written stories) MGI will take hazard mapping to a new level by visualizing narratives of survival, recovery, vulnerability, and adaptation. Off to a great start!

Data Collection

MGI plans to take an on-the-ground, participatory approach that records the stories of the citizens during hazard scenarios, including capturing how they have recovered. Participatory mapping pulls many disciplines together including social anthropology, geography, civil engineering, and agriculture, to gain a holistic understanding of how these sectors were impacted, have recovered, and became more or less resilient to hazards.

For instance, if we return to the perspective of villagers from Petite Savanne, where were they during the landslides of TS Erika, and how did they handle the situation? Did they relocate and how did their culture and lifestyle change because of it? How was their recovery further hampered by Maria? This type of research can aid in Government and regional disaster management decision-making. It is important for politicians to understand that while the aim is to relocate those most at risk (for example, in response to sea surge susceptibility in the west coast community of Canefield; see image 8) and rebuild more infrastructural resilient communities, our maps may also, show how the cultural practices of these communities can still be preserved and remain self-sufficient.

7. Flood Hazard map for two communities in Dominica, showing a 3-meter storm surge run-up flood simulation. (a) Canefield area with the airport; (b) Pottersville, Roseau. Map produced by G. Abraham, Auckland University of Technology 2020

Where can one find the most suitable site for relocation? What would be the best type of housing to fit their livelihoods (for instance, individual houses with small gardens vs. apartment complexes)? Mapping recoveries and resilience is also a tangible way of tracking Dominica’s goals of becoming one of the most resilient nations in the world. Hazards may set back development but resilience pushes it forward. This is where infrastructural improvements like the river levees along the Roseau River (see image 8), wider and higher bridges, houses built with four-sided roofs and safe rooms with concrete ceilings in homes are all some of the recoveries and improvements which MGI aims to visualize on the map.

8. Dominica’s capital Roseau in 2020 with its reconstructed bridges and river wall. Photos by Dominican photographer Yuri Jones www.yuriajones.com

Cultural practices and beliefs also play a major role in understanding risk management at the local level. During the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, many people shared stories of hearing spirits in the wind and referred to the forces of the storm as “evil”. What role does culture and folklore play in the local perception of the global climate change conversation and conversations about local vulnerability? This research aims to dive deeper into the conversation about these recoveries and the holistic question of resilience in Dominica.

By Gabrielle C Abraham, G.I.S. Research Associate, MGI

Gabrielle C Abraham brings hazard mapping GIS expertise and GIS to the CCC Project. She recently graduated with her MSc in Geospatial Science from the Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand, as a Commonwealth Scholar. Prior to this, she obtained her BSc in Geography (Hons) at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago. As a native of Dominica, Gabrielle is particularly excited to be a part of this project, and mapping the survivals and recoveries of the nation since Hurricane Maria and other storms. For more information on this project, feel free to email: Gabrielle Abraham at gabraham@monainformatixltd.com

9. Drone imagery of the city of Roseau. Photos by Dominican photographer Yuri Jones www.yuriajones.com